nalco group

bone, muscle & joint pain physio

BOOK NOW / WHATSAPP ABOUT YOUR PAIN OR INJURY

- ORCHARD 400 Orchard Road #12-12 Singapore 238875

- TAMPINES 9 Tampines Grande #01-20 Singapore 528735

- SERANGOON 265 Serangoon Central Drive #04-269 Singapore 550265

Home > Blog > Conditions > Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD)

Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD)

Osgood–Schlatter disease (OSD), also known as apophysitis of the tibial tubercle, is inflammation of the patellar ligament at the tibial tuberosity. It is characterized by a painful bump just below the knee that is worse with activity and better with rest. Episodes of pain typically last a few months.

One or both knees may be affected and flares may recur.

Risk factors include overuse, especially sports which involve running or jumping. The underlying mechanism is repeated tension on the growth plate of the upper tibia. Diagnosis is typically based on the symptoms. A plain X-ray may be either normal or show fragmentation in the attachment area.[2]

Pain typically resolves with time. Applying cold to the affected area, stretching, and strengthening exercises may help. NSAIDs such as ibuprofen may be used.[4] Slightly less stressful activity may be recommended.

About 4% of people are affected at some point in time. Males between the ages of 10 and 15 are most often affected. After growth slows, typically age 16 in boys and 14 in girls, the pain will no longer occur despite a bump potentially remaining. The condition is named after Robert Bayley Osgood (1873–1956), an American orthopedic surgeon and Carl B. Schlatter, (1864–1934), a Swiss surgeon who described the condition independently in 1903.

Signs and symptoms

Osgood–Schlatter disease causes pain in the front lower part of the knee.

This is usually at the ligament-bone junction of the patellar ligament and the tibial tuberosity. The tibial tuberosity is a slight elevation of bone on the anterior and proximal portion of the tibia. The patellar tendon attaches the anterior quadriceps muscles to the tibia via the knee cap.

Intense knee pain is usually the presenting symptom that occurs during activities such as running, jumping, squatting, and especially ascending or descending stairs and during kneeling. The pain is worse with acute knee impact.

The pain can be reproduced by extending the knee against resistance, stressing the quadriceps, or striking the knee. Pain is initially mild and intermittent. In the acute phase, the pain is severe and continuous in nature. Impact of the affected area can be very painful.

Bilateral symptoms are observed in 20–30% of people.

Risk factors

Risk factors include overuse, especially sports which involve

- running or

- jumping

The underlying mechanism is repeated tension on the growth plate of the upper tibia. It also occurs frequently in male pole vaulters aged 14-22.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made based on signs and symptoms.

Ultrasonography

This

test can see various warning signs that predict if OSD might occur.

Ultrasonography can detect if there is any swelling within the tissue as

well as cartilage swelling. Ultrasonography's main goal is to identify

OSD in the early stage rather than later on.

It has unique features such as detection of an increase of swelling within the tibia or the cartilage surrounding the area and can also see if there is any new bone starting to build up around the tibial tuberosity.

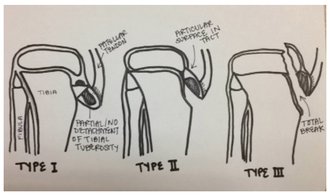

Types

OSD may result in an avulsion fracture, with

the tibial tuberosity separating from the tibia (usually remaining

connected to a tendon or ligament). This injury is uncommon because

there are mechanisms that prevent strong muscles from doing damage. The

fracture on the tibial tuberosity can be a complete or incomplete break.

- Type I: A small fragment is displaced proximally and does not require surgery.

- Type II: The articular surface of the tibia remains intact and the fracture occurs at the junction where the secondary center of ossification and the proximal tibial epiphysis come together (may or may not require surgery).

- Type III: Complete fracture (through articular surface) including high chance of meniscal damage. This type of fracture usually requires surgery.

Differential diagnosis

Sinding-Larsen and Johansson syndrome, is an analogous condition involving the patellar tendon and the lower margin of the patella bone, instead of the upper margin of the tibia.

Sever's disease is an analogous condition affecting the Achilles tendon attachment to the heel.

Prevention

One of the main ways to prevent OSD is to check the participant's flexibility in their quadriceps and hamstrings. Lack of flexibility in these muscles can be direct risk indicator for OSD.

Muscles can shorten, which can cause pain but this is not permanent. Stretches can help reduce shortening of the muscles.

The main stretches for prevention of OSD focus on the hamstrings and quadriceps.

Treatment

Treatment is generally conservative with rest, ice, and specific exercises being recommended (RICER).

Simple pain killers may be used if required such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) or ibuprofen. Typically symptoms resolve as the growth plate closes. Physiotherapy is generally recommended once the initial symptoms have improved to prevent recurrence. Surgery may rarely be used in those who have stopped growing yet still have symptoms.

Physiotherapy

Recommended physiotherapy focus efforts include exercises to improve the strength of the quadriceps, hamstring and gastrocnemius muscles, as well as regular stretches and improving muscle control through physiotherapy

Assessing

to understand or ascertain biomechanical factors that may cause or aggravate Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD) by sports physiotherapists

to prevent recurrence of pain and to maximise the performance

in their sport is recommended.

Bracing or use of an orthopedic cast to enforce joint immobilization is rarely required and does not necessarily encourage a quicker resolution. However, bracing may give comfort and help reduce pain as it reduces strain on the tibial tubercle.

Surgery

Surgical excision may rarely be required in skeletally mature patients.

In chronic cases that are refractory to conservative treatment, surgical intervention yields good results, particularly for patients with bony or cartilaginous ossicles. Excision of these ossicles produces resolution of symptoms and return to activity in several weeks.

After surgery, it is common for lack of blood flow to below the knees and to the feet. This may cause the loss of circulation to the area, but will be back to normal again shortly. A high pain may come and go every once in a while, due to the lack of blood flow.

If this happens, sitting down will help the pain decrease. Removal of all loose intratendinous ossicles associated with prominent tibial tubercles is the procedure of choice, both from the functional and the cosmetic point of view.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation focuses on muscle strengthening, gait training, and pain control to restore knee function.

Nonsurgical treatments for less severe symptoms include:

- exercises for strength

- stretches to increase range of motion

- cold therapy

- knee support and taping techniques

- knee braces

- anti-inflammatory agents

- and electrical stimulation to control inflammation and pain.

- Quadriceps and hamstring exercises prescribed by rehabilitation experts restore flexibility and muscle strength.

Education and knowledge on stretches and exercises is important.

Exercises should lack pain and increase gradually with intensity. The patient is given strict guidelines on how to perform exercises at home to avoid more injury. Exercises can include leg raises, squats, and wall stretches to increase quadriceps and hamstring strength.

This helps to avoid pain, stress, and tight muscles that lead to further injury that oppose healing.

Knee orthotics such as patella straps and knee sleeves help decrease force traction and prevent painful tibia contact by restricting unnecessary movement, providing support, and also adding compression to the area of pain.